The 50th anniversary of NASA’s historic landing on the Moon—this Saturday, July 20th—provokes a decidedly bittersweet feel. Certainly, this marks an appropriate moment to pause and celebrate a singular moment in our shared history, the first time humans ever set foot on another world. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins really did push back the frontier for all of humanity

And yet, for all that this technological and geopolitical tour de force achieved, there has been a decided lack of follow through by the US spaceflight enterprise since Apollo 11. On such an anniversary, this raises uncomfortable questions. Why have we not gone back? Was the Apollo Program really America’s high water mark in space? And will we actually return in the next half century?

Why we went

Beginning with Sputnik in 1957 and continuing through the flights of Yuri Gagarin and other cosmonauts, the Soviet Union ticked off an impressive succession of “firsts” in space during the middle of the Cold War. As the United States waged a hearts-and-minds campaign against the Soviets around the world, technological superiority represented a key battlefront.

Newsworthy space achievements offered critical wins for the Russians. As Charles Fishman's entertaining new book One Giant Leap notes, Gallup polling in 1960 showed that large majorities of people in countries such as Great Britain, France, West Germany, and India believed the Soviet Union would lead the world in science during the 1960s.

Shortly after becoming president in 1961, John F. Kennedy sought ideas to demonstrate American, rather than Soviet, technological superiority. His first notion did not concern space exploration, rather he wanted to find a means of desalinating sea water to provide a fresh source of drinking water for the developing world. This was deemed not splashy enough.

-

President Kennedy delivers his "Decision to Go to the Moon" speech on May 25, 1961 before Congress.NASA

-

The President and First Lady watch Alan Shepard's flight on TV in the White House, on May 5, 1961.NASA

-

President John F. Kennedy presents astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr. with NASA's Distinguished Service Medal Award in a Rose Garden ceremony on May 8, 1961, at the White House.NASA

-

Shepard, again, at the White House ceremony. Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson and NASA Administrator James E. Webb are in the background.NASA

-

President John F. Kennedy (left) visits Mercury's Flight Control Area a few days after John Glenn's flight in February 1962. To Kennedy's right are Glenn and astronaut Alan Shepard.NASA

-

John Glenn, standing next to the Friendship 7 capsule in which he made his historic orbital flight, meets with President John F. Kennedy. Mrs. Glenn stands next to her husband.NASA

-

President John F. Kennedy, astronaut John Glenn, and General Leighton I. Davis ride together during a parade in Cocoa Beach, Fla., after Glenn's historic first U.S. orbital spaceflight.NASA

-

In this photograph from 1962, President Kennedy attends a briefing given by Major Rocco Petrone during a tour of Blockhouse 34 at the Cape Canaveral Missile Test Annex. Also in attendance are Vice-President Lyndon Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.NASA

-

This 1961 photo shows JPL Director Dr. William H. Pickering, (center) presenting a Mariner spacecraft model to President Kennedy, (right). NASA Administrator James Webb is directly behind the Mariner model. Mariner 2 launched on Aug. 27, 1962.NASA

-

President Kennedy and Wernher von Braun walk through facilities at Marshall Space Flight Center in 1962.NASA

-

Dr. Wernher Von Braun explains the Saturn system to President Kennedy at Complex 37 while the president tours the Cape Canaveral Missile Test Annex on Nov. 16, 1963.NASA

-

President John F. Kennedy, right, gets an explanation of the Saturn V launch system from Dr. Wernher von Braun, center, at Cape Canaveral in November 1963.NASA

-

President Kennedy visits The Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston in 1962.NASA

-

During his 1962 speech at Rice University, Kennedy declared: "Many years ago the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why did he want to climb it. He said, 'Because it is there.'"NASA

Eventually, Kennedy was persuaded that America would have to go tit-for-tat with the Soviets in space. Because the Russian space program has flown so far ahead of NASA, Kennedy had to choose a goal far enough into the future that the United States would have a chance to catch up—and this became the genesis of the audacious Moon landing program.

Before his assassination, Kennedy had already begun to rethink the America-first nature of the space program. After the Cuba missile crisis, he envisioned space as a potential uniter of the two superpowers, and in 1963 he proposed a joint mission to the Moon between NASA and the Soviet Union. However, just six days after his death that November, new president Lyndon B. Johnson announced in a nationwide television address that he would rename NASA’s Florida launch site in Kennedy’s honor. The program soon became entrenched as a way to honor the slain leader.

Thus, the Apollo Program was born out of a desire to strengthen the geopolitical standing of the United States during the Cold War, and it was sustained in the memory of its author’s untimely death.

Why we failed to return

Whenever the White House directs NASA on a program to send humans back to the Moon, or Mars, or elsewhere, one of the first things the agency does is scramble together advisory panels to provide messaging advice. How, best, can the need for such exploration be explained to the public? How can NASA justify costs in the tens or hundreds of billions of dollars?

There is little economic justification. By going to Mars, NASA will not generate new wealth for the United States. And while humans in space can explore with more dexterity than robots, that hardly justifies a hundred-fold cost increase, or the ultra-high safety risks of sending people instead of machines to explore distant worlds. This leaves NASA with fuzzy explanations, often along the lines of it is human nature to explore and expand our horizons.

The American public has been unmoved by such appeals. A recent poll found that only about one-in-four Americans believe sending humans to the Moon or Mars is "very" or "extremely" important, and this poll is consistent with other surveys of public opinion since the end of the Apollo program. Large majorities of Americans say the space program should mostly focus on protecting Earth from asteroid strikes, studying this planet, and the robotic exploration of other worlds.

The hard reality is that, since the Cold War, the human exploration of deep space has not been part of the strategic national interest. NASA had already sent humans to the Moon, and the United States was universally viewed as the global science superpower. How would landing more men and women on the Moon change that?

Unfortunately, difficult though it was to reach, the Moon was low-hanging fruit. There isn’t anywhere else for humans to reasonably go in deep space that could make a similar statement. The engineering challenge of mounting a human mission to Mars—complete with pre-supplying the planet, surviving the radiation environment, providing surface power, launching from the Martian surface, and safely returning to Earth—represents an order of magnitude greater challenge. As NASA astronaut Don Pettitt says, if the toilet breaks on the International Space Station, NASA can send a replacement up. If a toilet breaks on the way to Mars, the crew dies.

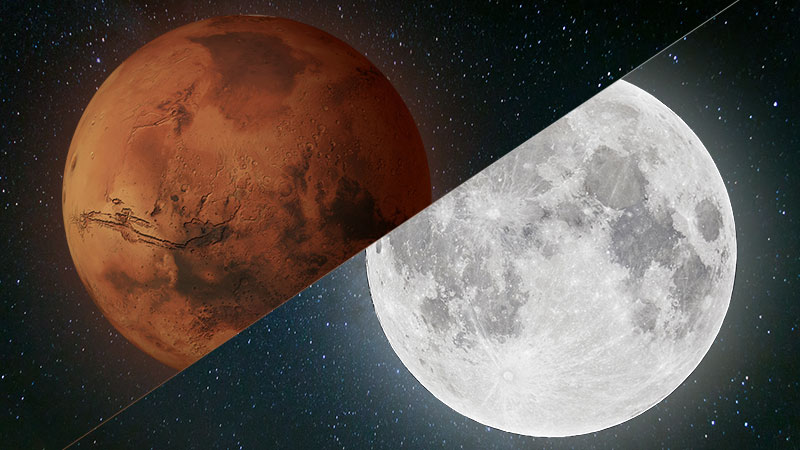

In contemplating a deep space exploration program, NASA has been stuck between Scylla and Charybdis. A choice to return to the Moon would be met by a “been there, done that” attitude from most Americans, whereas a decision to embark upon a multi-decade, enormously expensive program to send humans to Mars would be met with a “just send the robots” response. So for the last 30 years, presidential administrations have bounced between the Moon and Mars for NASA’s human exploration program.

Crippling lack of unity

From a practical standpoint, the post-Apollo aerospace community has been hampered by a great fracturing of desires. During the 1960s, pretty much everyone, from the president through the contractors and the agency’s work force, lined up behind landing on the Moon. Today, there is no unity of purpose among human spaceflight stakeholders.

The White House, generally, has wanted some big human achievement in space. Dating back to George H.W. Bush in 1989, every president except Bill Clinton has established either a lunar return, or a Mars landing, as the overarching goal of NASA’s human spaceflight program. But although NASA is an executive agency, the President cannot set its budget. The White House must get Congressional consent.

Accordingly, Congress has often been a major impediment. It generally has parochial priorities, as individual members want to stack funding and jobs into the NASA field centers and contractor hubs in local districts and states. For example, the chairman of the Senate’s Appropriations committee, Alabama Republican Richard Shelby, has near absolute control over the agency’s budget. As a result, most of the major aerospace companies have expanded or opened offices or factories in Alabama.

The field centers themselves often seek to consolidate their power and funding into local fiefdoms. Even during Apollo, there was a rivalry between Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama and the Johnson Space Center in Texas. But these tensions were exacerbated during the blame game that followed the loss of space shuttle Challenger in 1986. NASA centers want to make progress, certainly, but they don’t want to cede power to other centers in order to do so.

The large, legacy aerospace contractors are also jealous of their funding and influence. When the space shuttle program ended in 2011, the major players went along with this decision because they smoothly transferred into new programs. Boeing, responsible for the shuttle orbiter, took over the core stage of the Space Launch System rocket. Orbital ATK, which built the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters, would so the same for the SLS rocket. Aerojet Rocketdyne would continue making shuttle engines for the SLS. Lockheed Martin, which built the external fuel tank, had the Orion spacecraft. And so on.

Today, there is yet another community with increasing influence. Advocates for new space, most publicly Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, seek to leverage private funding and modern technology to lower the cost of reaching space. They are battling with the legacy aerospace contractors for influence and funding, with mixed success.

Each of these different entities—the White House, Congress (which is itself often divided between Republican and Democratic interests), NASA’s top-heavy bureaucracy, legacy aerospace companies, and new space interests—are all pushing and pulling civil spaceflight in various directions. The end result is that no one can ever really agree where to go, how to go, and how to pay for it.

Will we ever go back?

The last three US presidents have been more or less committed to sending humans beyond low-Earth orbit, and NASA has engaged in building the "capabilities" for a deep-space exploration program (principally the Orion spacecraft and two large rockets, the Ares V and then the Space Launch System rocket).

As glacial as the progress has been on these vehicles—humans are unlikely to use them to fly into deep space before the early or mid-2020s—the costs have been equally staggering. NASA has spent $50 billion over the last 15 years on deep space vehicle development alone.

During a notable space policy speech in Huntsville, Alabama in March, Vice President Mike Pence summarized the problem this way:

“After years of cost overruns and slipped deadlines, we’re actually being told that the earliest we can get back to the moon is 2028,” Pence said. “Now, that would be 18 years after the SLS program was started and 11 years after the President of the United States directed NASA to return American astronauts to the Moon. Ladies and gentlemen, that’s just not good enough. We’re better than that.” Pence has since pushed NASA to return to the Moon by 2024.

The Trump administration settled on a Moon-first exploration plan, and for good reasons. There is an emerging recognition that water ice exists at the lunar poles in large quantities, and harvesting this could eventually provide a valuable source of fuel for deep-space propulsion. A return to the Moon also supports nascent commercial companies that want to harvest these resources. This has become the Artemis program, which has promise but also faces political peril.

There are a couple of reasons to believe that the current effort may have some legs. One is the revolution in private efforts to develop low-cost rockets led by SpaceX. By reducing the cost of access to space, commercial companies are opening the door to a future of in-space refueling, staging in low-Earth orbit, and different approaches to the everything-on-one-rocket approach of Apollo.

The second factor is that, for the first time in decades, NASA and the United States have a major rival in outer space in China. The Asian country views space much the way Kennedy did in the 1960s, as a means of demonstrating its technological capability to the world and placing itself on equal footing with the United States. What better way to do that than send Chinese taikonauts to the lunar surface?

This is the path China is on, if not in 2030, then probably in the early 2030s. China already is seeking to peel off NASA’s longtime partners in Europe to join its efforts to build a space station and tag along for eventual missions to the lunar surface.

Therefore, if the White House and Congress don’t get serious about identifying an exploration program most people can agree on—one which uses modern technology and which they agree to fund fully—then America’s half century of greatness in space will prove to be transient rather than permanent.

On the 50th anniversary of America, if not humanity's, crowning scientific achievement, that outcome feels like it'd be a real disservice to Neil, Buzz, and Mike.

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Half a century after Apollo, why haven't we been back to the Moon? - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment